The Role of Fate in the Medieval World

Fate, luck, destiny, providence; all words to describe the unseen power that seems to control our life events. Who you believe is the unseen power differs in this day and age. In the Middle Ages, however, everyone was pretty much on the same page. Life’s ebbs and flows are dictated by the Rota Fortunae, the Wheel of Fortune, and the goddess Fortuna.

Why did I get sick? Why did the crops fail? How come the king chose him over me? From time immemorial people sought answers. Things like this, so out of our control, have always needed an explanation. Why not blame it on the gods?

Fate, Greek and Roman Style

The Greeks and Romans found the idea of events happening without some type of guiding hand unsettling. It was a lot more comforting to think gods and goddesses were dealing out the cards, even if they weren’t always nice about it. Enter the Greek Moirai, and their Roman counterparts the Parcae. We know them as the three fates.

As destiny incarnate, these three sisters control a person’s life from birth to death. Clotho, as in cloth, is the one spinning the threads of life. She spins and spins until Lachesis, the “Apportioner of Lots” measures it with her rod. Finally, there is Atropos. She gets the honors of deciding how each person will die, and with her shears cuts the thread of life.

The Greek poet Hesiod wrote about the fates in his Theogony in the 8th century. Their personalities continued to evolve from then on. Literary works depicted then as old, ugly women. Shakespeare’s Macbeth is a well-known example. In visual depictions, however, they tended to be much more attractive.

Hesiod tells us about another Greek goddess of fortune, Tyche. Depictions often show her blindfolded or balancing on a ball to convey the uncertainty and change of fortune. For the Roman’s this was the goddess Fortuna. Her role in Rome was much greater than Tyche to the Greeks. It was Fortuna who became most popular in the Medieval Period.

Boethius and His Date with Fate

It was through the Roman philosopher Boethius, and his book The Consolation of Philosophy, that the Medievals really became familiar with Fortuna. In fact, most of what Medievals knew about Greek philosophy was courtesy of Boethius’ writings. Certainly, the man knew what he was talking about when it came to fate. He wrote The Consolation while imprisoned on false charges of treason. Before landing in jail he was at the pinnacle of society, mingling with the Ostrogoth ruler Theoderic the Great.

In the midst of his suffering, Boethius has a discussion with Lady Philosophy. He was pondering and complaining about his fall from grace, as one is wont to do in such situations. Philosophy steps in to remind him worry is for the weak. Truly, destiny is in the hands of Fortuna, a fickle and untrustworthy woman. Fortunes will rise and fall at her whim and all one can do is enjoy the ride. It’s through the Lady Philosophy we glimpse the famous wheel of fortune. “Inconstancy is my very essence, says the wheel. Rise up on my spokes if you like but don’t complain when your cast back down into the depths.” Fortuna certainly cast Boethius down since he ends up executed.

Fortune in the Medieval World

For the common medieval man, it all made sense. Serfs who were bound to the land depended on their lord to protect them and keep the peace. Fate with all its fluctuations and foibles ruled their existence. Even at the highest levels of society fortunes could rise and fall at a moment’s notice. Just look at our dear Boethius after all. Fate holds everyone hostage. And so the idea of someone controlling fate continued to be popular.

It took a while for the Christianized Medieval world to fully embrace Fortuna and her wheel, however. St. Augustine, for example, wrote against her in his book The City of God saying:

“How, therefore, is she good, who without discernment comes to both the good and to the bad?… It profits one nothing to worship her if she is truly fortune… let the bad worship her…this supposed deity”

St. Thomas Aquinas echos this rejection again in the 1200s. Ultimately, in the 1300s, Dante manages to baptize her as a truly Christianized Fortuna. Yes her manners tend to look pagan, he concedes, but really let’s not lose sleep over the whole thing. After all, she has no power to act on her own; she is merely administering God’s divine will.

Finally, everyone could breathe a sigh of relief. Fortune could exist within the framework of the church. With a little tweaking anyway.

Fortune In Art

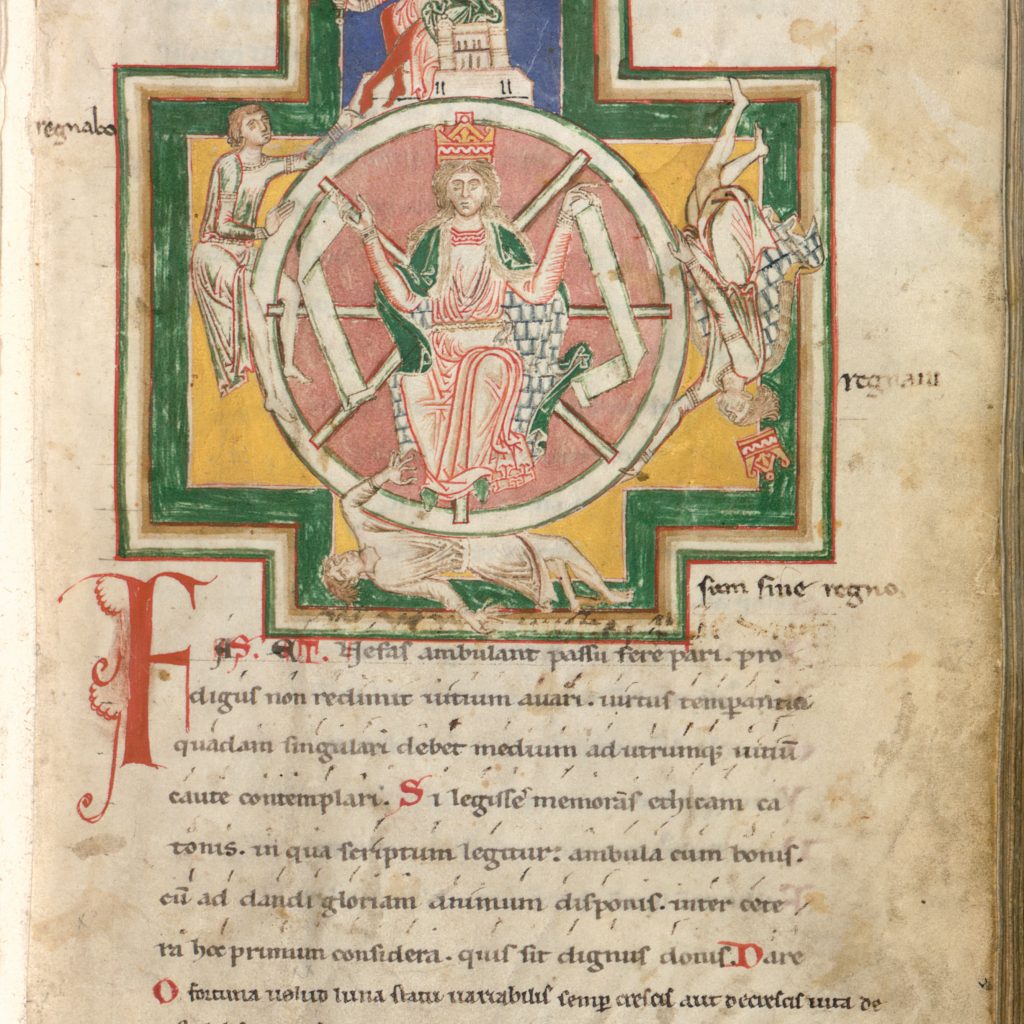

By the 12th century, The image of Fortuna is solidified. She stands near a mechanical wheel with a lever that she controls. Attached to the wheel are four figures, often dressed like kings, each with different names. On the left is regnabo (I shall reign), on top is regno (I reign) to the right regnavi (I have reigned) and at the bottom lies the unfortunate sum sine regno (I am without a kingdom). The image of the wheel becomes very popular in medieval art and literature. Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, The morality play Everyman, Arthurian romances, and even Machiavelli’s The Prince. all refer to fortune’s wheel.

As a Christian symbol, the wheel could remind everyone of the follies of ambition. Focus on the higher things, it says. Forgo the love of the temporal. You’ll be better for it in the end. The Abbott of Fécamp went so far as to make an actual revolving wheel so his monks could contemplate the ever-changing fate of man.

Fortuna and her wheel showed up in manuscripts as well. The image below comes from the 12th century. You can clearly see her turning her wheel and the kings whose fate she is adjusting. Appropriately, the image is part of a commentary on the book of Job.

Fortune goes to Church

Rose windows incorporated into Cathedral designs are another example of the Christianized wheel. These big round stained glass windows are iconic symbols of gothic architecture. The hope was Churchgoers would use it to meditate on the benefits of a well-ordered soul. Christ becomes the center of the wheel, and the Christian who keeps him at the center of their soul remains in peace and harmony with him. The image could also be found on church frescos and exterior sculptures.

The theme of fortune continued in European art and literature well past the middle ages. Heck, it’s even been the theme of game shows. Whatever you believe in, fate or free will, here’s hoping we’re all at the top of the wheel in the coming new year.

Sources:

The Tradition of the Goddess Fortuna in Medieval Philosophy and Literature, Howard Rollin Patch Smith College

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes Vol. 20, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec. 1957), pp. 248-297 (53 pages)Published by The Warburg Institute

Leave A Comment