Apparently Eating Mummy Makes You Healthy

If you lived in the medieval world herbs and spices would be your ally. Assuming you could afford them, they would be in almost everything you cooked and even drank. After all, they added flavor and had great health benefits. Anything that went by the name herb was fresh and green. Spices, on the other hand, were imported luxuries brought from strange lands. They were dried, brown and wrapped in a mystical, exotic aura. With a definition like that, what qualified as a spice was open to lots of interpretation. Take tutty for instance. Classified as a medicinal spice, tutty was chimney residue. Of course, not just any chimney could work, it had to come from Alexandria. As weird as tutty is, I’d rather have that than momie. Why? Because they took momie from embalmed bodies.

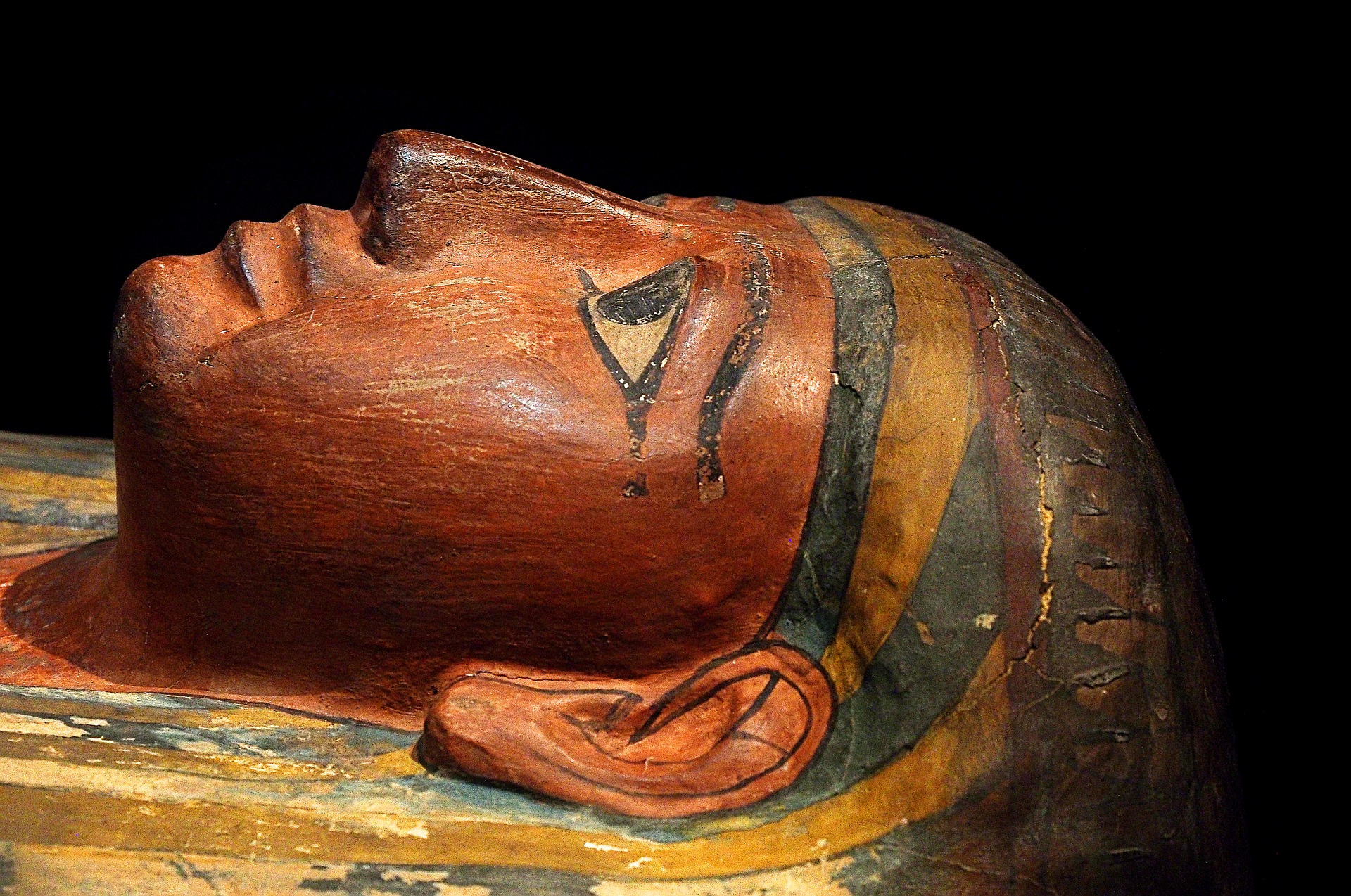

According to A drug handbook from 1166, momie (or mumia) was a “spice” collected from the tombs of the dead in Egypt. Not just any part would work, however. For example, feet would get you nowhere. It was head and spine fluid mixed with embalming spices that caused the miracles. According to the text, the best quality momie came from corpses not entirely dried out, with a foul odor and pitch like consistency. Momie was considered quite useful for abscesses, eruptions, fractures, concussions, paralysis, epilepsy and a slew of other health issues. It was decocted in anything from elder or saffron to butter or milk.

Skull is Good Food

Lest you think using human remains was some weird thing medievals did, think again. The practice went well into the 16th and 17 centuries, and it wasn’t just something strange and esoteric. Kings, priests, and scientists all employed the aid of the dead. King Charles II had a remedy he took with him everywhere. He called it—oh so creatively—The Kings Drops and he made it with skulls diluted in alcohol. Even that smart guy Leonardo Di Vinci got in on it:

“We preserve our life with the death of others. In a dead thing insensate life remains which, when it is reunited with the stomachs of the living, regains sensitive and intellectual life.”

DaVinci

As time went on, the original idea of momie got modernized. People decided a new mummy was just as good as an old one. Of course, there were still some rules to follow. Take the advice given in The Treasury of Drugs from 1690. This book was written specifically as a drug handbook for merchants so you know it’s accurate. According to the book, the best skulls are those of men who died a violent death, such as in a war or a criminal execution, and were never buried. It also seems to favor skulls from Ireland; very clean and white don’t you know.

Red Heads Work Wonders

Don’t like the taste of Irish skull? Well, how about redheads? Around the age of say, 24? According to Oswald Croll’s 1608 remedy, they work pretty well. You might find the recipe a bit time consuming though.

Take the fresh corpse of a red-haired, uninjured, unblemished man, 24 years old and killed no more than one day before, preferably by hanging, breaking on the wheel or impaling… Leave it one day and one night in the light of the sun and the moon, then cut into strips. Sprinkle on a little powder of myrrh to prevent it from being too bitter. Steep in spirit of wine for several days. As the foulness of it causes an intolerable humidity in the stomach, it is a good idea to macerate the mummy with oil.

Oswald Croll

It’s not the Mummy’s Fault- its Pissaphalt

All this is very interesting, if not odd. Yet there’s one more twist to the story. The mummy that was so highly prized for its curative powers, was the wrong type of mummy. It was never meant to be a real dead person, let alone the day-old corpse of a red-headed guy.

It all started with Pissaphalt which was according to an 1869 definition: earth pitch, a soft black bitumen of the consistency of tar considered to be a combination of naphtha and asphalt. This pissasphalt had long been renowned in the near east as a great remedy. When traded, it went under the name mummia because it had an uncanny resemblance to the material used in the Egyptian mummification process.

Accept no Substitutions

After a while, people must have got tired looking for pissasphalt and found it much easier to just swipe the material from their locally grown mummies. Abd Allatif, an Arabian historian and physician writing in 1203 said The mummy found in the hollow corpses of Egypt, differ but immaterially from the nature of mineral mummy and where any difficulty arises in procuring the later may be substituted in its stead.” However, it’s important to note Abd was referring to the bituminous deposits from the mummification process—not the body itself. It was this slight—but somewhat important—little point that got lost in the translation.

How well this last bit of information was known is hard to say, but for the marketers in Egypt, it didn’t matter. Business was booming, and that was what really counted. One Arab writer in 1424 described a crowd of over 800 people who had been robbing tombs and were in the process of boiling their finds to extract the oils. The results were to be sold to the Franks for 25 pieces of gold for every 100 pounds. By 1588 people were getting lazy. They just brought the bodies to the markets in Cairo and sold them whole. A few short cuts later and we end up with Irish criminals.

By the 18th century, ingesting the remains of the local criminals was becoming a questionable practice. Old habits die hard, however. Momie was commercially available until 1924.

Shari | 16th Oct 19

Wow, this is crazy! Fascinating.

nicolvalentin | 16th Oct 19

It’s certainly not what we would think of as medicine today–and I’m glad! Thanks for stopping by Shari!

Lauren | 16th Oct 19

Wow! I had no idea. Kinda creepy but cool. Could be the new/old CBD!

nicolvalentin | 18th Oct 19

Wow, I never thought of that connection! Thanks for sharing.:-)